Naaalala ko noong 2nd year hayskul ako at nanuod ako ng The Ring yung orihinal na bersyon. Corny kasi nung remake ng Kano, masyadong hi-tech na masyado at nawawala ang "takot" factor kasi nag-iingles. Di ako nagdidiscrimate ah. Ayun nga, nanuod ako tapos di nako nakatulog eh may pasok pa 'ko nun. Hindi na 'ko nakatulog. Masyado nang umukit sa isipan ko si Sadako. Katakot. Isipin mo lang na nakatayo si Sadako sa labas ng bintana ng kwarto mo (na nangyari sakin). Kahit pagsakay ko sa dyip naiimagine ko siya na nakatayo sa labas ng bintana ko. Oo, imposible nga kasi umaandar yung dyip pero 'yun na ang takbo ng isip ko. Parang mala-mananaggal na si Sadako at kung saan saan na siya lumalabas. Halos mabaliw nako non. Makalipas ang ilang araw, nawala 'rin sa isip ko si Sadako. Hallelujiah!

Sigurado ako na nangyari na sa inyo ang ganito, di 'man sa pamamagitan ng panunuod sa isang palabas, pero nangyari na.

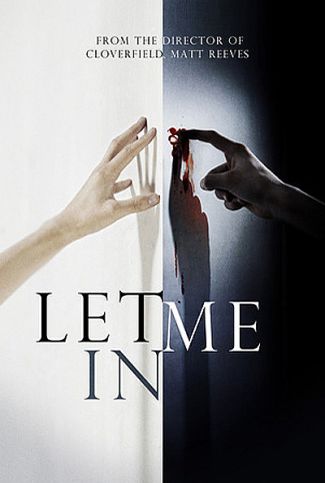

Nagkaroon kami ng film viewing sa school noong isang beses, ang pamagat ng pelikula ay "Let Me In" sa direksyon ni Matt Reeves. Kakaiba nga lang kasi 'pag isinalin sa wika natin ay "Papasukin mo Ako", parang iba ang dating. Nakakatawa. Parang palabas pangpornograpiya PERO di ka na makakatawa 'pag napanuod mo na ito. May pagkasuspense thriller ang theme ng pelikula at na-establish ito ng maayos. Mas gusto ko magpokus dun sa istorya ng pelikula. Ano nga bang pinagkaiba nito sa ibang mga horror films? Bukod sa may bampirang superhuman na napakaathletic, kapansin pansin din ang paggamit nila sa isa sa mga nakakakuhang pansing emosyon ng tao -- ang kagustuhang magkaron ng kaibigan. Lahat naman tayo nagnanais na magkaron ng mga kaibigan na pwede nating masandalan mas lalo na sa mga oras ng lugmok tayo at parang tinakluban o sinukuban ng mundo. Walang manhid na tao na okay lang mabalewala. Sa totoo lang, di ko masisisi si Owen dahil maging ako man ay naghahanap ng mga totoong kaibigan na hindi sakin mang-iiwan. 'Dun siguro kami nagkakapareho sa sugat o bubog ng buhay namin. Walang gustong mag-isa, walang gustong mapag-kaisahan ng mga tao sa paligid niya. Walang gustong makaramdam na walang naroroon para sa kanya. yan' ang mga bagay na naramdaman ni Owen kaya kung sino man ay magpakita sa kanya ng konting kabaitan ay bibigay siya kahit ang magpakita pa sa kanya ng kabaitan ay isang bampira na pumatay ng tao para lang mabuhay. Obviously, di maganda ung gawaing ganun. 'Di na actually kailangang itanong pa kasi buhay ng tao ang pinag-uusapan. Simple lang ang storya, tungkol ito sa taong naghahanap ng kaibigan dahil kailangan niya ng masasandalan. Ang pinagkaiba lang ng istoryang ito sa normal na istoryang ito ay bampira na nauulol sa amoy ng dugo ay ang kanyang nahanap. Weird noh? Ang active ngang bampira nung babae, di mo aakalaing bampira. Haha Ang nakakagulat sa pelikulang ito ay kung gaano kalakas ang pangangailangan ng isa tao ng kaibigan sa napakamurang edad. Ako yung tipo ng tao na nagpopokus sa istorya pero napapansin ko kung may kakaiba sa musical scoring at sa mga anggulo ng kamera, ngunit sa palabas na ito ay wala akong napansin kaya masasabi kong ang musical scoring at mga shots ng camera ay naayon lamang sa palabas at nakatulong ito para makabuo ng bagong mundo na para lamang sa pelikulang 'Let Me In'.

Synopsis:

The title of “Let Me In” might be understood as a plea to the audience. Even if you think you’ve had enough of the vampirization of popular culture — “Twilight,” “True Blood,” “The Vampire Diaries” and so on — find room in your heart for this one. And though it teases out the usual horror movie sensations of dread and anxiety and eyes-averted disgust, this movie also makes a direct and disarming play for affection, eliciting in viewers something akin to the awkward, resilient tenderness that is its subject. Vampire romanticism is nothing new, of course. Millions of us, not just teenage girls, have followed the courtship of Bella Swan and Edward Cullen through every deep breath and smoldering glance. But the love story in “Let Me In,” between two 12-year-olds, one of them a blood-craving undead pixie named Abby, is both more intense and more innocent.

The subtext of the relationship is not sexuality, as it is in “Twilight” or “True Blood,” but rather the loneliness of children and their often unrecognized reservoirs of rage. Abby (Chloë Grace Moretz) and her pal, a trembling, big-eyed boy named Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee), are fragile and quiet but also capable of horrifying violence.

“Let Me In,” Matt Reeves’s worthy and honorable remake of “Let the Right One In,” Tomas Alfredson’s Swedish adaptation of the novel by John Ajvide Lindqvist, is disturbing because it takes you inside the minds of its young main characters, Owen in particular. Ignored and harangued at home by his mother — his parents are in the midst of a divorce — Owen is easy bait for bullies at school. He compensates for his powerlessness by bingeing on candy and shutting himself in his room, where he spies on the neighbors with a telescope and acts out sadistic serial-killer fantasies in front of the mirror.

“Are you scared, little girl?” he whispers, brandishing a kitchen knife and calling his imaginary victim exactly what his locker room tormentors call him.

The little girl who does arrive in Owen’s life — moving into the next apartment in his shabby little complex with a shambling, put-upon adult guardian (Richard Jenkins) — becomes the boy’s ally in a pact of mutual protection. “We can’t be friends,” she tells him when they first meet in the courtyard where he likes to sit alone at night, eating Now-and-Laters.

But of course they do, even as their moments of easy companionship are punctuated by a series of gruesome crimes, committed by the man Owen assumes is Abby’s father in order to feed her appetite for human blood. When the poor man messes up these hunting missions, as he often does, Abby must gather her own prey, which gives her (and Mr. Reeves) a chance to show off some creepy computer-aided monster skills.

The story holds a few surprises, but what makes “Let Me In” so eerily fascinating is the mood it creates. It is at once artful and unpretentious, more interested in intimacy and implication than in easy scares or slick effects. Mr. Reeves also made “Cloverfield,” a movie whose genuine formal cleverness was overshadowed by an annoying pseudo-documentary gimmick — recalling “The Blair Witch Project” and anticipating“Paranormal Activity” — as well as by some very annoying characters.

With “Let Me In” the director demonstrates, in addition to impressive horror movie chops, a delicate sensitivity and a low-key visual wit. Much of the action takes place in semi-darkness (the sunlight-allergic Abby’s preferred ambience), and Mr. Reeves and his cinematographer, Greig Fraser, warp and blur the images, using shallow focus to convey the isolation and disorientation of the vulnerable children. Michael Giacchino’s score glides effortlessly from jarring sonic freakouts to lush swells of melodramatic orchestration.

All of it — and the quite haunting performances of Ms. Moretz and Mr. Smit-McPhee — allows you to see how Abby and Owen construct their own world in the face of various threats and misunderstandings.

There is, in addition to the bullies and the parents, a dogged cop played by Elias Koteas, who thinks some kind of Satanic cult must be responsible for the bloodletting. There is not, refreshingly enough, a lot of pseudoscholarly demonological lore. No Volturi or rival werewolf clans; no excursions into the sociology or mythology of the undead; no Internet searches turning up images of medieval woodcuts and esoteric Latin text.

No Internet at all, for that matter, since “Let Me In,” following the lead of the original, takes place in 1983. David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” is on the radio, along with Culture Club, and Ronald Reagan is on television, lecturing the nation about good and evil. The period evoked seems to be a sad, anxious time. The setting — Los Alamos, N.M., perhaps for reasons having more to do with local tax incentives than with anything else — is drab and wintry, like the Sweden of Mr. Alfredson’s original, though the emotional tone is more American emo than Nordic melancholy.

The early-’80s cultural touchstone that “Let Me In” brought to my mind — indirectly and perhaps perversely — was Steven Spielberg’s “E.T.” Mr. Smit-McPhee looks a bit like Henry Thomas, and both play boys from broken families living in the Southwest whose lives are changed by the intervention of a supernatural (and potentially immortal) friend. That one is a warm science-fiction fable and the other a dark horror film makes the similarity more striking, since both movies begin with, and build their fantasies against, the terror and fury of childhood.

“Let Me In” is rated R (Under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian). It has swearing and gore.

LET ME IN

Written and directed by Matt Reeves; based on the novel “Lat den Ratte Komma In” by John Ajvide Lindqvist; director of photography, Greig Fraser; music by Michael Giacchino; production design by Ford Wheeler; costumes by Melissa Bruning; produced by Simon Oakes, Alex Brunner, Guy East, Tobin Armbrust and Donna Gigliotti; released by Overture Films. Running time: 1 hour 55 minutes.

WITH: Chloë Grace Moretz (Abby), Kodi Smit-McPhee (Owen), Richard Jenkins (the Father) and Elias Koteas (the Policeman).

Synopsis:

The title of “Let Me In” might be understood as a plea to the audience. Even if you think you’ve had enough of the vampirization of popular culture — “Twilight,” “True Blood,” “The Vampire Diaries” and so on — find room in your heart for this one. And though it teases out the usual horror movie sensations of dread and anxiety and eyes-averted disgust, this movie also makes a direct and disarming play for affection, eliciting in viewers something akin to the awkward, resilient tenderness that is its subject. Vampire romanticism is nothing new, of course. Millions of us, not just teenage girls, have followed the courtship of Bella Swan and Edward Cullen through every deep breath and smoldering glance. But the love story in “Let Me In,” between two 12-year-olds, one of them a blood-craving undead pixie named Abby, is both more intense and more innocent.

The subtext of the relationship is not sexuality, as it is in “Twilight” or “True Blood,” but rather the loneliness of children and their often unrecognized reservoirs of rage. Abby (Chloë Grace Moretz) and her pal, a trembling, big-eyed boy named Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee), are fragile and quiet but also capable of horrifying violence.

“Let Me In,” Matt Reeves’s worthy and honorable remake of “Let the Right One In,” Tomas Alfredson’s Swedish adaptation of the novel by John Ajvide Lindqvist, is disturbing because it takes you inside the minds of its young main characters, Owen in particular. Ignored and harangued at home by his mother — his parents are in the midst of a divorce — Owen is easy bait for bullies at school. He compensates for his powerlessness by bingeing on candy and shutting himself in his room, where he spies on the neighbors with a telescope and acts out sadistic serial-killer fantasies in front of the mirror.

“Are you scared, little girl?” he whispers, brandishing a kitchen knife and calling his imaginary victim exactly what his locker room tormentors call him.

The little girl who does arrive in Owen’s life — moving into the next apartment in his shabby little complex with a shambling, put-upon adult guardian (Richard Jenkins) — becomes the boy’s ally in a pact of mutual protection. “We can’t be friends,” she tells him when they first meet in the courtyard where he likes to sit alone at night, eating Now-and-Laters.

But of course they do, even as their moments of easy companionship are punctuated by a series of gruesome crimes, committed by the man Owen assumes is Abby’s father in order to feed her appetite for human blood. When the poor man messes up these hunting missions, as he often does, Abby must gather her own prey, which gives her (and Mr. Reeves) a chance to show off some creepy computer-aided monster skills.

The story holds a few surprises, but what makes “Let Me In” so eerily fascinating is the mood it creates. It is at once artful and unpretentious, more interested in intimacy and implication than in easy scares or slick effects. Mr. Reeves also made “Cloverfield,” a movie whose genuine formal cleverness was overshadowed by an annoying pseudo-documentary gimmick — recalling “The Blair Witch Project” and anticipating“Paranormal Activity” — as well as by some very annoying characters.

With “Let Me In” the director demonstrates, in addition to impressive horror movie chops, a delicate sensitivity and a low-key visual wit. Much of the action takes place in semi-darkness (the sunlight-allergic Abby’s preferred ambience), and Mr. Reeves and his cinematographer, Greig Fraser, warp and blur the images, using shallow focus to convey the isolation and disorientation of the vulnerable children. Michael Giacchino’s score glides effortlessly from jarring sonic freakouts to lush swells of melodramatic orchestration.

All of it — and the quite haunting performances of Ms. Moretz and Mr. Smit-McPhee — allows you to see how Abby and Owen construct their own world in the face of various threats and misunderstandings.

There is, in addition to the bullies and the parents, a dogged cop played by Elias Koteas, who thinks some kind of Satanic cult must be responsible for the bloodletting. There is not, refreshingly enough, a lot of pseudoscholarly demonological lore. No Volturi or rival werewolf clans; no excursions into the sociology or mythology of the undead; no Internet searches turning up images of medieval woodcuts and esoteric Latin text.

No Internet at all, for that matter, since “Let Me In,” following the lead of the original, takes place in 1983. David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” is on the radio, along with Culture Club, and Ronald Reagan is on television, lecturing the nation about good and evil. The period evoked seems to be a sad, anxious time. The setting — Los Alamos, N.M., perhaps for reasons having more to do with local tax incentives than with anything else — is drab and wintry, like the Sweden of Mr. Alfredson’s original, though the emotional tone is more American emo than Nordic melancholy.

The early-’80s cultural touchstone that “Let Me In” brought to my mind — indirectly and perhaps perversely — was Steven Spielberg’s “E.T.” Mr. Smit-McPhee looks a bit like Henry Thomas, and both play boys from broken families living in the Southwest whose lives are changed by the intervention of a supernatural (and potentially immortal) friend. That one is a warm science-fiction fable and the other a dark horror film makes the similarity more striking, since both movies begin with, and build their fantasies against, the terror and fury of childhood.

“Let Me In” is rated R (Under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian). It has swearing and gore.

LET ME IN

Written and directed by Matt Reeves; based on the novel “Lat den Ratte Komma In” by John Ajvide Lindqvist; director of photography, Greig Fraser; music by Michael Giacchino; production design by Ford Wheeler; costumes by Melissa Bruning; produced by Simon Oakes, Alex Brunner, Guy East, Tobin Armbrust and Donna Gigliotti; released by Overture Films. Running time: 1 hour 55 minutes.

WITH: Chloë Grace Moretz (Abby), Kodi Smit-McPhee (Owen), Richard Jenkins (the Father) and Elias Koteas (the Policeman).